Volume 4 Issue 2, Article

Tome 4 numéro 2, Article

Making it ‘Local’: Community data journalism for health justice

Shirley Roburn

Abstract

This paper reports on a multi-modal case study of the journalism of The Local, a new journalism start-up with a health equity mandate, during six months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings indicate that The Local’s reporting had a concrete, meaningful impact in improving health equity outcomes in COVID-19 public health efforts in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) during the time period studied. The Local accomplished this using a unique approach. The Local’s Code of Ethics and its Race, Representation and Equity Commitment shaped the magazine’s structure, which in turn influenced reporting. The Local applied a health-equity lens to its pandemic data journalism. It followed up on the health inequities which surfaced by having racialized journalists, representative of the communities they serve, pursue deep features, often with a solutions journalism approach.

Keywords: community journalism, health justice, data journalism, journalism start-up, hyperlocal journalism, pandemic reporting, COVID-19 communication, alternative media, digital journalism, race in journalism

Rendre ‘Locale’ : un cas de journalisme de données en service du justice en matière de santé communautaire

Résumé

Cet article présente une étude du journalisme de The Local, une jeune entreprise de journalisme numérique axée sur l’égalité des chances en matière de santé, durant les six mois de la pandémie de COVID-19. Les résultats indiquent que les reportages de The Local ont eu un impact concret et important sur l’amélioration des résultats d’équité en santé dans le cadre des efforts de santé publique liés à la pandémie de COVID-19 dans la grande région de Toronto pendant la période étudiée. The Local a accompli cela grâce à une approche unique. Le code d’éthique de The Local et ses engagements en matière de race, de représentation et d’équité, ont influencé la structure du revue, ce qui a ensuite influencé les reportages. The Local a appliqué une perspective d’équité en santé à son journalisme de données au sujet de la pandémie. Le périodique a suivi les inégalités en santé que ce journalisme a éclairé par des reportages approfondis, souvent avec une approche de journalisme de solutions, réaliser par des journalistes racialisés, représentatifs des communautés qu’ils servent.

Mots-clés : journalisme d’engagement, jeune entreprise de journalisme, journalisme hyperlocal, reportage sur les pandémies, communication COVID-19, médias alternatifs, journalisme numérique, race dans le journalisme

ARTICLE

Making it ‘Local’: Community data journalism for health justice

Shirley Roburn

INTRODUCTION

According to The Local News Research project, the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada was directly responsible for the permanent shuttering of 44 community newspapers and the temporary closing of fifteen more (Lindgren et al., 2020). It also led to a decline in alternative weeklies, and an increase in papers shifting all or some of their editions to online only. A rare bright spot in the pandemic journalistic landscape has been an increase in online digital news startups.

Since the 2010s, journalism scholars have turned their attention to digital news start-ups globally, including studies in North America (Callison & Young, 2020; Schaffer 2010, 2013), Europe (Bruno & Nielsen 2012; Usher 2017), Asia (Wu, 2023), and Australia and New Zealand (Simons 2013; Downman & Murray, 2018). As Downman and Murray (2018) highlight, emergent digital journalisms come in many forms, including “niche journalism, participatory journalism, citizen journalism, alternative journalism, slow journalism, geosocial journalism, engaged journalism, reciprocal journalism – the list goes on” (p.1). Although new journalism start-ups are playing an increasingly vital role in the overall journalism landscape, research into the subset of journalism start-ups that centre data journalism is relatively scant (Wu, 2023), and even scarcer when one focuses on community or local journalism start-ups with a social purpose mandate, as opposed to for-profit start-ups.

This paper shares results from the second phase of a multi-modal research project concerning the impact that one particular health justice focused community digital journalism startup, quarterly magazine The Local, had in spring and summer of 2021. As COVID-19 vaccinations began to be made available to the general population across the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), The Local focused its data journalism and feature reporting on inequities in the vaccination rollout, and how these played out in poorer health outcomes in underserved neighbourhoods. Through social media analysis, news content analysis, and interviews, the research aimed to determine if and how The Local had an impact on pandemic health outcomes in the GTA.

The Local’s reporting exerted appreciable influence in several ways. Its clear, consistent data-driven animations and graphics of neighbourhood level inequalities in pandemic health outcomes supported elected officials and public health bureaucrats to take a health justice focused approach to the COVID-19 vaccination rollout. Its Hot Spot Tracker directly influenced the choices of local officials responsible for locating and operating COVID-19 vaccination clinics. Finally, the expanded reach of The Local’s award- winning deep dive features on the experiences of the pandemic in underserved neighbourhoods, framed from a social determinants of health perspective, correlates with mainstream papers increasing their reporting on these communities, and shifting their narratives towards a greater focus on health equity.

LITERATURE REVIEW

COVID-19 and declining community news coverage

The alarming decline of local and community newspaper coverage in Canada in recent decades is commonly constructed as an economic and technological crisis (Shattered Mirror, 2017), as well as a crisis of concentration of ownership (Winseck, 2017). Daily newspaper advertising revenue declined by half in the decade beginning in 2006; concomitantly, amalgamation of media outlets brought more than half of major Canadian dailies under a single company, Postmedia. Thousands of job cuts have augured a decline in the diversity and depth of local news coverage, which was subsequently exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. These patterns are in keeping with the pandemic’s impact on journalism globally, in which local and community news has been particularly hard hit (Quandt and Wahl- Jorgensen, 2021). Quandt and Wahl-Jorgenson (2021) argue that the pandemic acted as a critical moment for journalism, challenging the relevance of existing business models and throwing into sharp relief the challenges and changes facing the journalism industry and the climate it operates within.

Crisis as opportunity: the rise of digital news start-ups and data journalism

Rather than just crisis, Quandt and Wahl- Jorgenson also frame this critical moment as a time of opportunity and transformation, noting the rise of both new journalism start-ups and the field of data journalism. Journalism research has aimed to catalogue emergent data visualization practices, and what niches data journalists and data journalism are carving out within newsrooms (Wu, 2023; Widholm & Appelgren, 2022; Engebretsen, Kennedy, Weber, 2018; Young, Hermida & Fulda, 2018). For example, studies indicate that during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, data journalism “rendered COVID-19’s potential developments accessible to policy makers and the public” (Pentzold et al., 2021, p. 1367), engaging readers with updated scientific and public health information and presenting sophisticated modelling in formats digestible to the lay person. Recent work highlights how the pandemic instigated a leveling up in the overall quality and pervasiveness of data journalism in newsrooms (Kirk, 2024), and ushered in changes in practice as data journalism became more integrated in the day-to-day of journalism (Tong, 2024).

As digital data revolutionizes everything from online platforms, to marketing, to science and engineering, journalism researchers are probing larger questions about how data visualization and data journalism alter the people, places, processes, and products of news making (Hermida & Young, 2019; Bounegru & Gray, 2021). Germane to this case study, attention is increasingly focused on how data science and data mapping take place within matrices of power where intersectionality shapes impacts on particular populations. Theorists argue variously for new forms of data feminism (Tacheva, 2022; D’Ignazio & Klein, 2020), Indigenous data sovereignty (Walter et al. 2020), and other intersectional approaches to counter algorithmic bias (Chun, 2021; Buolamwini, 2023). Academics, activists, and journalism professionals seek to apply data collection and visualization methods, including those of data journalism, that can reveal inequality and concretize social justice disparities in accessible graphics and maps (Jeppesen & Sartoretto, 2023; Lowan-Trudeau, 2021; Appelgren, 2019).

Since the 2010s, a developing body of work has analyzed the growth of digital news start-ups globally, even as many legacy news outlets are in decline (Bruno & Nielsen 2012; Callison & Young, 2020; Downman & Murray, 2018; Schaffer, 2010, 2013; Simons, 2013; Usher, 2017; Wu, 2023). In Canada, the proliferation of digital news start- ups offers a rare bright spot in the snapshots of declining local and community newspaper outlets documented by The Local News Research Project since 2018.1The Local News Research Project website (https://localnewsresearchproject.ca/) documents the state of local news in Canada through multiple means, including a variety of “news maps,” various written publications and newspaper articles, and downloadable data. As Callison and Young (2020) note, compared to their legacy news competitors, these relatively recent digital start-ups “actively work(s) to extend and experiment with economic models, partner with non-journalists, and privilege underserved, feminist, and diverse perspectives” (p.141). In 2020, as part of measures to address the collapse of journalism in Canada, the Canadian government made changes to tax law to certify “Registered Journalism Organizations” as not-for-profit entities that receive some of the tax benefits of charities, including the ability to issue charitable donation receipts (which give tax breaks to recipients). The Narwhal and The Local, the first organizations to receive this new designation, are both journalism start-ups that, fitting with Callison and Young’s (2020) findings, are experimenting with different mixes of revenue sources in search of a sustainable economic model. Callison and Young (2020) also emphasize that relatively little journalism research responds to, or foregrounds, “persistent critiques related to gender, race, indigeneity and colonialism,” (p. 5), although they argue that these critiques are necessary to understanding and addressing declining journalism readership. Yet one of the differences between legacy media and much of the subset of small Canadian journalism start-ups is that these start-ups often have mandates and organizational practices that respond to such critiques, despite an overall tendency for the mainstream digital journalism space to reproduce employment precarity and exclusions along racial and gendered lines (Cohen & Clarke, 2024).

Community and social-purpose digital news start-ups

Taking a comparative international perspective, Motta (2022) documents robust support networks built by community journalism start-ups, sometimes in partnership with major funders, that provide different forms of assistance, from funding to trainings to technology and even financial planning services, specifically for outlets by and for marginalized communities. Motta also notes that, catalyzed by broader changes to journalism practice and markets during the pandemic, community based digital journalism start-ups have turned to “constructive” and solutions-based approaches as part of a paradigmatic shift arising partially from a more engaged approach that forged closer ties to communities and audiences. If researchers such as Motta (2022), and Callison and Young (2020) are correct, digital journalism start-ups with a social purpose and/or marginalized community focus are qualitatively different from mainstream journalism not only in their makeup and mandate, but in their day-to-day journalistic practice. What does this mean in terms of data journalism? How might data journalism be enacted differently, and have different impacts, as it is practiced within the context of small social purpose digital journalism start-ups? This case study broaches these questions through an in-depth study of the impact of the pandemic health justice reporting of one such digital news start-up, The Local.

Specific context

It is necessarily to touch briefly upon the specific context of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, in order to understand how the media, and specifically The Local, could have an impact on vaccination policy in the time period studied. Fitzpatrick et al. (2022) lay out in detail the health systems, policies, and chains of command that governed the roll-out of COVID-19 vaccinations as they first became available in Ontario. Germane to this discussion,

Pandemic-management decisions, including vaccine rollout, were led by a combination of public health officials, political leaders, and logistics and leadership committees; however, as evidenced by the composition of Ontario’s COVID-19 Vaccination Distribution Task Force, there was no public health involvement in this leadership and no members with public health expertise (Ontario, 2020d). (Fitzpatrick et al., p. 29)

In practice, the Premier and cabinet were closely involved in high-level decision making, and decisions reflected a political calculus. One illustrative example is the Office of the Premier’s announcement in April 2021 of measures to shut down children’s playgrounds and give police “arbitrary powers” (Nasser & Powers, 2021) to stop, question, and fine anyone outdoors. These measures were rescinded less than 24 hours later due to political backlash. Reporter Mike Crawley (2021) concluded that the government was “not acting on recommendations from the science table—such as mandating paid sick days and paring back the list of essential workplaces—while imposing measures no health advisers had actually recommended,” due to its internal polling indicating a need to be seen taking action (para. 15). This episode illustrates that the government was sensitive to public pressure, but also to business interests concerned about negative economic impacts from pandemic measures. The government response to the pharmacy desert controversy (discussed later) illustrates a similar dynamic: in response to public pressure, the second phase of the pharmacy vaccine pilot specifically targeted virus “hot spots” in Toronto and Peel (Robertson, 2021). However the government did not take up advice from the Ontario Pharmacists Association that there be a more equitable split to include vaccinations being allotted to independently owned pharmacies rather than to large chain pharmacies largely owned by Loblaws, a company that the Canada Health Coalition has repeatedly accused of cozying up to governments in order to forward plans to have more of health care activities (such as vaccinations) outsourced and privatized (Van Horne, 2024; Dowson, 2024).

In this context, public health officials working within existing structures were in a difficult position: the default position of government on pandemic health measures often differed from what public health science and policy would consider best practice. Yet to speak out strongly could easily backfire, both by politicizing issues further rather than pulling policy back towards public health perspectives, and by compromising a speaker’s employment if the speaker was seen by their employers as not respecting the sensitivities of their position. A more effective corrective, as occurred with the playgrounds directive, was pressure, whether public pressure or pressure from constituencies the government wished to keep on side. In the case of vaccination, public pressure was needed not only to have equity measures enacted, but to ensure the government continued to prioritize vulnerable populations and communities rather than reverting to an ‘equal’ allotments of vaccination doses that did not take into consideration that some populations were much more at risk than others. It was also required to support the involvement of the public health apparatus, and its expertise, in the initial campaign when vaccines became available (rather than, for example, for-profit pharmacies being the main conveyor of vaccines). However, at the outset of the January to June 2021 time period of this study, dominant narratives in pandemic news reporting tended to support the status quo (Loreto, 2021), rather than mainstream news taking a more critical role in interrogating public health implications of specific government policies.

In contrast, pandemic equity concerns easily fit within the core mandate of The Local, launched in May of 2019 as an independent online quarterly magazine after two years of incubation at OpenLab, a healthcare innovation studio within Canada’s largest research and teaching hospital network. The Local originated as a storytelling project designed to foreground social determinants of health concerns to health policy decision makers by giving voice to “neglected voices of Toronto’s diverse neighbourhoods” (OpenLab, n.d.). In the words of Executive Editor Nick Hune-Brown,

when the pandemic started, it felt like, all of a sudden, our interest was the only story in the globe, like, what social determinants make your health worse, that was the story of the pandemic. So everyone was writing in our territory. (personal communication, August 25, 2022)

METHOD

An earlier paper (Chen & Roburn, 2025) reports on the first phase of this multi-modal study of The Local’s coverage of the COVID-19 vaccination roll-out in the GTA in the spring and summer of 2021. This thematic analysis of tweets by the magazine’s official accounts and The Local’s key journalists found that The Local took “a unique journalistic approach that prioritized hyper-local, data-informed, and affective storytelling over the traditional norm of journalists as detached observers and information providers” (Chen & Roburn, 2025). This second phase of the study focuses on qualitative methods to further probe this journalistic approach at a more granular level. A further quantitative element, detailed later, emerged to follow up on one conclusion from the interview process. Additionally, in follow-up interviews The Local provided both precise quantitative data on website and social media traffic, and written documentation backing up its claims of impact on the vaccination roll-out in Toronto. In this case study, circulation figures are expressed as ratios or in general terms in order to keep proprietary data confidential. Similarly, private communications shared with this researcher are only discussed in the most general of terms, with the focus on the material from the interviews as the main elaboration of these points.

Research questions included:

Q1. What were the key characteristics of The Local’s pandemic reporting?

Q2. What role did The Local’s reporting and the work of The Local’s reporters play in reframing debates about the COVID-19 vaccination rollout? Did The Local’s reporting impact the journalism landscape and mainstream reporting in the GTA?

Q3. What can we learn about how The Local had influence: how did The Local’s journalism reach different constituencies?

Q4. What does the case study of The Local highlight as far as what is needed to support a more diverse community journalism landscape in Canada?

Between September 2022 and May 2023, 15 semi-structured interviews were conducted over videoconferencing software. The interview process was approved by the York University’s Office of Research Ethics. Interviewees included staff of The Local, other journalists, and a selection of influential officials (elected and appointed) and critics involved in Toronto’s vaccine rollout in 2021 (Table 1).

Table 1. Interviewee Breakdown

| Category | Female | Male |

| Local journalists/ editor | 1 | 2 |

| Other journalists | 4 | 2 |

| Health justice advocates and government officials | 3 | 3 |

The Local’s Editor-in-Chief, Executive Editor, and reporter Fatima Syed, who wrote two influential long-form features about the pandemic and vaccination campaign in Peel region, were interviewed. Other reporters who were solicited for interviews were either health or data journalism- focused reporters at major mainstream Canadian news outlets (two newspapers and the CBC, Canada’s public broadcaster), with an effort made to include racialized reporters and women. Locating an appropriate selection of health-focused officials and health justice critics began with observing which officials and health advocates interacted with The Local’s tweets. However, it quickly became evident that focusing on the amount of interaction with The Local tweets analyzed in the first phase of the study reproduced biases by under-representing women and minorities, who were less likely to be vocal on Twitter (now called X) on a highly politicized topic, due to the disproportionate level of threats, harassment, and hate that research demonstrates these groups face on online platforms (Lingiardi et al., 2020; Mirrlees, 2021; Gillespie, 2018).2In Canada, anti-vaccination discourse became an important talking point for the far right, leading to convoys of truckers blocking a border crossing and taking over the streets of Ottawa for several weeks. See https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/key-events-canadas-trucker-protests-against-covid-curbs-2022-02-19/ and https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/how-american-right-wing-funding-for-canadian-trucker-protests-could-sway-u-s-politics. For the role of Russia in stoking these protests over social media, see https://doi.org/10.21810/jicw.v5i3.5101

Additionally, those with official roles in the vaccination rollout also limited their interactions over Twitter. Snowball sampling was instead used to help identify appropriate officials. The sampling of health justice advocates drew from people who had a Twitter presence and interacted with The Local, but rather than focus on those who interacted the most, the sampling included racialized people and women who had an overall lower interaction level on Twitter, but substantive public communicative activities through other forums, such as mainstream media or, in the case of the Gritty Nurses, their own podcast. Half of the health justice advocates identified as racialized either publicly or during the interview.

Interviews ranged from 20 to 78 minutes in length, averaging 50 minutes long. Participants were asked about: their professional experience during the pandemic; their experiences of media coverage of the pandemic and of the 2021 vaccination campaign; their knowledge and impressions of The Local and of The Local’s pandemic coverage, including specific Local infographics and feature reports; and, for those involved in media, suggestions they had for government supports and policy to foster a more robust local journalism landscape. Three interview templates were used to solicit input on these themes, with some question framing varying for The Local journalists, for other journalists, and for those active in the health justice field. For example, health justice advocates were asked about their roles as communicators during the pandemic, while journalists were asked about their role as media producers.

Interviews were coded based on thematic analysis, a method that derives critical understanding of underlying themes through open-ended, inductive analysis (Hawkins, 2018; Braun 2019). This approach is described in more detail in Chen and Roburn (2025) as it pertained to the initial, social media focused phase of the research. For the interviews phase, codes were determined through an iterative process by the author and a research assistant. Relevant passages were grouped and reviewed within a given code, with the text analyzed by this author for key points of agreement and disagreement, and the relative prominence of themes.

A key finding, repeated by multiple interviewees, was the claim that The Local’s feature report “You Can’t Stop the Spread of the Virus if You Don’t Stop it in Peel” by Fatima Syed, published on April 22, 2021, was a watershed moment that shifted media coverage of the pandemic in the GTA towards a greater focus on health equity and on how the pandemic was impacting poorer, racialized neighbourhoods mainly located outside the city core. This finding was investigated through collecting pandemic news coverage in The Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail for six weeks before and six weeks after April 22, 2021, and comparing articles by length and using frame analysis (Winslow, 2017), to see if there were differences in the amount and type of coverage of the pandemic in Peel region before and after Syed’s Local feature.

FINDINGS

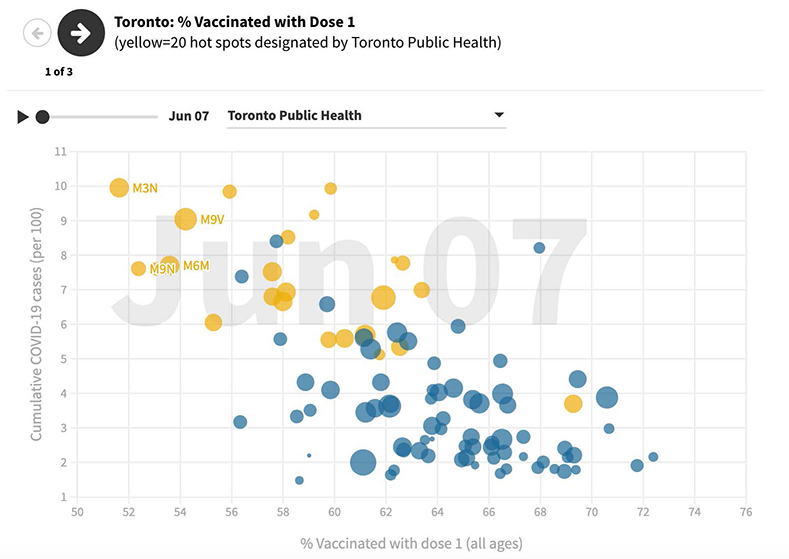

The Local’s reporting had a meaningful impact in improving health equity outcomes in COVID-19 public health efforts in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) during the time period studied. Evidence of this impact will be discussed in this section. Thematic findings, many of which illustrate the why and how of this impact, are offered in following sections. The Local’s impact was twofold. Firstly, The Local’s coverage influenced government and public health officials in their policy choices. Discussing the rollout of the City of Toronto’s COVID-19 vaccination campaign, City Councillor Joe Cressy, the Chair of the Toronto Board of Health, and member of the City of Toronto’s COVID-19 Strategic Command Team3The Strategic Command Team was tasked with coordinating the city-wide response to the pandemic. and Immunization Task Force, described that The Local “played a pretty important role from a data led, evidence-based standpoint in highlighting inequities, in helping to spur governments to address them.” This perspective was further affirmed by an anonymous interviewee with high-level roles on various tables charged with developing and implementing vaccination policy in Toronto. This interviewee described The Local’s Hot Spot Tracker, regularly disseminated over Twitter, and viewed by tens of thousands4The Local shared that the total viewership over the Tracker’s active lifetime was equivalent to the viewership for an entire multi-story regular edition of The Local. The Tracker also circulated widely through being heavily featured in Tai Huynh’s personal Twitter feed—raw data from the earlier social media analysis phase of this project showed 13 of his 100 most like Tweets discussed hot spots, with several linking directly to the Tracker., as “kickstart(ing) the conversation” in support of what became known as the Sprint strategy, a vaccine equity program launched in Toronto to allocate and deliver vaccination doses to disadvantaged neighbourhoods (personal communication, February 24, 2023). The animated Tracker graphed cumulative COVID-19 cases (y-axis) against the percentage population with a first vaccination dose in each forward sortation area (defined by the first three letters and numbers ofa postal code), with the data points being coloured either yellow for those that were designated ‘hot spots’ by Toronto public health, or blue (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Local’s Hot Spot Tracker images, June 7 and June 20, 2021

At a time when COVID-19 vaccinations were mainly delivered through mass immunization clinics, The Local’s reporting clearly demonstrated the success of pilot efforts at community vaccination clinics, as vaccination rates then rose in the targeted ‘hot spot’ neighbourhoods. According to the official, “in Thorncliffe Park . . . we brought vaccine into the area, into a local mosque, (and) delivered high doses of vaccine to thousands of people. And it’s through that Hot Spot Tracker that The Local actually showed how this neighborhood went from being one of the least vaccinated neighborhoods in Toronto, to above average . . . when you see data that compelling, it’s hard not to act on it” (personal communication, February 24, 2023).

These examples from the interviews reflect a broader reality. In follow-up exchanges with The Local, Executive Editor Nicolas Hune- Brown shared multiple examples of public health officials with important responsibilities in the vaccine roll-out infrastructure, including the Sprint strategy, thanking The Local in writing and attributing specific wins, such as getting the ‘green light’ for vaccination clinics in underserved neighbourhoods, or for an increase in priority and resourcing to accelerate vaccination efforts in a particular ‘hot spot.’ In private communication with this author, other staff and Board members of The Local have also referred to conversations and communications of a similar nature with health officials.

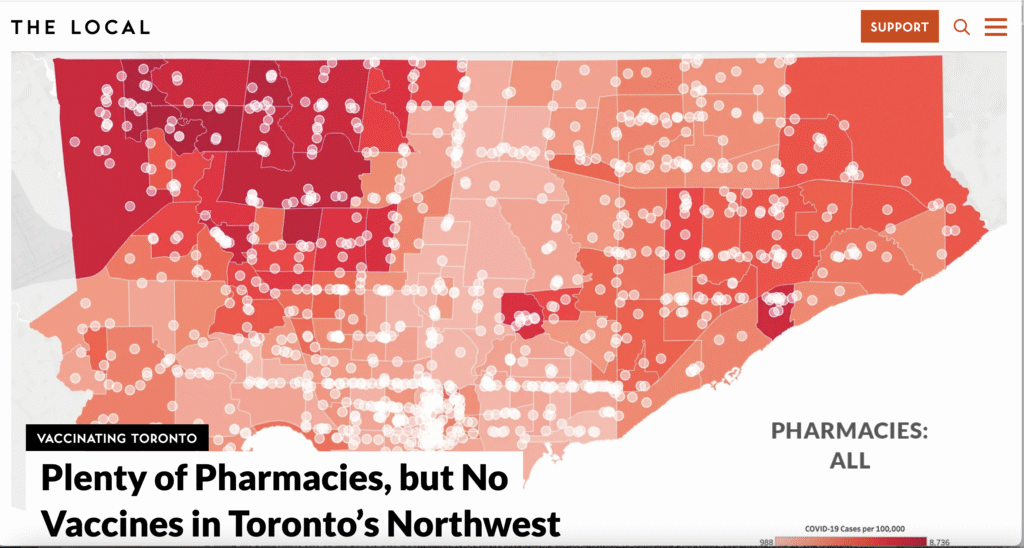

Public health officials described The Local’s coverage as making irrefutable, data-based arguments showing inequities in vaccination distribution, for example through the aforementioned Hot Spot Tracker, and through a “pharmacy desert” map 5This was the colloquial name used by interviewees for the data visualization. The visualization mapped densities of COVID-19 infections per forward sortation area, while toggling between displaying all pharmacies in the city and showing only pharmacies which were giving COVID-19 vaccinations. Disadvantaged areas with high covid rates did not lack for pharmacies, but a strikingly low percent offered covid vaccinations compared to pharmacies in wealthier neighbourhoods.(Figure 2), and by demonstrating the successes of the Sprint strategy both through the Hot Spot Tracker and through reporting on the community vaccination clinics. They also described this coverage as being regularly seen over Twitter by key health professionals, administrators, bureaucrats and government officials, thus generating political pressure in support of equity focused allocation of vaccination doses and resources within the larger vaccination campaign. The Local’s Vaccinating Toronto series, which rolled out over spring and summer 2021,6During the pandemic, one of the pivots The Local made to be more responsive in the moment to changing pandemic conditions was to experiment with publishing an issue as a ‘series’ over a period of weeks as individual articles were completed. had a viewership of hundreds of thousands of people, four times higher than the viewership for any other Local issue in either 2020 or 2021.7The exact figures are proprietary, although the author has access to them.

Figure 2. Maps posted by The Local comparing all pharmacies versus pharmacies with vaccines

The highest single-day spike in viewership, in the tens of thousands, corresponded with the publication of Tai Huynh’s “Behind the Sudden Drop at Toronto’s Mass Immunization Clinics,” a data-rich and, also, in situ exploration of how, months into Toronto’s vaccination campaign, much more poorly resourced, grassroots-oriented pop-up vaccination clinics in underserved neighbourhoods were substantially out-performing large, well-funded city-run vaccination clinics. Other stories on the vaccine roll-out in Peel and Toronto had similar high page views.

Local data visualizations that were multi-week- or month-long projects, regularly updated, kept attention and political pressure on real-time progress of efforts to mitigate COVID-19 spread, highlighting what was working (and thus should be supported) and what was less successful. City Councillor Joe Cressy described reflections he had when The Local’s reporting showed that despite a well-resourced strategy of 300 school-based vaccination clinics in hard-hit neighbourhoods in the first two weeks of vaccinations for five- to11- year-olds, ‘hot spot’ neighbourhoods continued to have the lowest vaccination rates for this age group. While Toronto Public Health “built an equity-driven model from day one,” campaigners had to adjust their thinking from disappointment “that the kids in Rosedale still got vaccinated at higher rates than the kids in Rexdale,” to “we didn’t fix structural inequality on the basis of a well-run five- to 11-year-old vaccine campaign, but we’ve mitigated a lot of risk” (personal communication, November 27, 2022).

The other main impact of The Local’s work was that it shifted the amount and tenor of mainstream media coverage of how the COVID-19 pandemic was unfolding in communities in greater Toronto. Many journalists described how The Local’s coverage of underserved communities such as Peel, and of marginalized constituencies, such as essential workers, not only impressed them but prompted them to reflect upon how their own journalism could be better. Some specifically stated that The Local’s leadership influenced newsroom pandemic coverage. For example, Nora Loreto, a prominent newspaper and magazine freelancer who also wrote a book about the pandemic response in Canada, asserted that The Local “drove analysis, often The Globe and Mail was chasing them, or CBC was chasing them” (personal communication, September 30, 2022). Another health reporter from a major news outlet called The Local’s reporting a “game changer,” and described it as coming up repeatedly in team meetings about pandemic reporting, shortly before managers at her news outlet decided to dedicate substantially more resources to reporting on the pandemic in Peel and other hard-hit communities.8In cases where reporters worked at outlets that could be seen as direct competitors, and they are essentially comparing their own employer’s work unfavourably to The Local’s, I have omitted identifying details. Multiple public health advocates and journalists pinpointed Fatima Syed’s article “You Can’t Stop the Spread of the Virus if You Don’t Stop it in Peel,” as a key inflection point in pandemic coverage. In the announcement jointly awarding Fatima Syed and Tai Huynh a 2022 Press Freedom Award for The Local’s COVID-19 coverage, World Press Freedom Canada stated of Syed, “Her groundbreaking series of articles led the national media to focus on Peel” (World Press Freedom Canada, 2022). Table 2 lists awards The Local won either for elements of its pandemic coverage or for its overall coverage in 2021; as these awards are given by journalism-focused organizations and are geared towards a community of journalists and the journalism industry, they can be taken as further recognition that The Local was understood by both new and legacy media to have played an influential role in pandemic coverage. The Press Freedom Award is particularly of note because it is given out for “outstanding achievements by Canadian media workers who produce public- interest journalism while overcoming secrecy, threats and intimidation, refusal to comply with freedom of information requests, or other factors that suppress information gathering” (World Press Freedom Canada, 2022). The Local was able to break silences in an atmosphere where the government was either not gathering or actively suppressing certain unfavourable information,9This claim was made by both Nora Loreto and an anonymous health journalist interviewee, referencing specific examples such as concerns about reporting on COVID-19 cases in long-term care homes. and where health workers and other essential workers were often afraid to speak out.

Table 2: Accolades for the Local for 2021 reporting

| Winner | Award type | From | For |

| Fatima Syed and Tai Huynh | 2022 Press Freedom Award | World Press Freedom Canada | COVID-19 coverage |

| Aparita Bhandari | 2021 Silver: Best News Coverage, Community Publication | World Press Freedom Canada | COVID-19 coverage |

| Tai Huynh | 2021 Honorable Mention: Best News Coverage, Community Publication | Digital Publishing Awards | COVID-19 coverage |

| Kat Eschner | 2021 Silver: Best Feature Article, Short | Digital Publishing Awards | COVID-19 coverage |

| Simon Lewsen | 2021 Gold: Best Feature Article, Long | Digital Publishing Awards | COVID-19 coverage |

| The Local | 2021 Gold: General Excellence in Digital Publishing, Small | Digital Publishing Awards | 2021 reporting, general |

| Danielle Groen | 2022 Short Feature Writing | National Magazine Awards | COVID-19 coverage |

| The Local | 2022 Honorable Mention: Issue Grand Prize | National Magazine Awards | COVID-19 coverage |

| Nicolas Hune-Brown | 2022 Editor Grand Prize | National Magazine Awards | COVID-19 coverage |

Thematic findings

The Local captured so much attention because of its outstanding coverage of the pandemic from a health equity standpoint. The following sections expand on key themes in the interviews which describe the specifics of what was original and impactful about The Local’s reporting; the characteristics of The Local that allowed it to operate as it did; some of the multipliers that helped The Local’s work spread; and some of the structural limitations to this type of journalism.

Data journalism

(with) The Local, there has been this amazing leveraging of that data that I think has . . . exposed the hardships faced by a lot of different groups and communities, in ways that were so impactful. It was really easy to see, in black and white. It makes it hard for people to look away. Even if they have nothing in common with those groups, they are in a different income bracket, and their lives don’t intersect at all. It’s harder when you see in black and white, in print. Like, this is the plight these groups were facing. And I think it also just showed us how rich and valuable data is in our reporting, and how desperately we need this going forward. (personal communication, October 13, 2022)

–A health reporter interviewee, referring to the use of forward sortation/postal code data in The Local’s reporting10The interviewee began by saying a few outlets had done data in the pandemic exceptionally well, then they mentioned The Local by name.

Local Executive Editor Nicolas Hune-Brown described how “in our very first issue as an independent publication, we created this interactive map that just tried to talk about disparities between neighborhoods like that’s, that’s in our DNA” (personal communication, August 25, 2022). From the outset, The Local approached data journalism through a health equity lens. This was groundbreaking. The Local pursued hyperlocal journalism in which, at a very granular level, data journalism surfaced stark population health disparities between different communities. This disrupted mainstream narratives of collective suffering during the pandemic: clearly, some communities suffered more. For example, the “pharmacy desert” map showed plainly that, rather than people from poorer, racialized neighbourhoods being unwilling to get vaccinated, they had much higher structural barriers to accessing vaccinations. In overlaying socioeconomic indicators with public health indicators at a neighbourhood level, and tracking these variables over time, The Local surfaced trends and gaps that mainstream media outlets had not been able to parse. This data was concretely useful, not just to policy makers, but to parents, workers, and to generally anyone impacted by the pandemic. The Local’s most popular dynamic data visualization, the School Tracker, was consulted by tens of thousands of parents.11Tai Huynh described the page views as in the 100,000 range, and since the thousands of data points were reported to The Local by parents themselves (how many COVID-19 positive tests there had been that week at individual GTA schools), it is likely that most viewers were parents.

Clear, up-to-date, and relevant data journalism was part of what built reader trust in The Local and in Editor-in-Chief Tai Huynh, who regularly tweeted Local data visualizations and on-the- scene photos from vaccination clinics. Health justice advocate Naheed Dosani described The Local’s reporting as

digging deep at the roots of access to care for communities during the pandemic, and particularly communities that were hardest hit. Giving real objective information and visualization of that information to really allow us to appreciate how inequitable things really were for certain groups and certain people . . . the rigor and detail was impressive, the utilization of data and graphics to present that data was superbly unique and innovative. And it (was) just something I didn’t see in other media outlets. (personal communication, November 30, 2022)

Some of this work could be thought of as public service journalism: The Local was providing information that perhaps governments should have, but did not. For example, The Local set up a RAT tracker (for Rapid Antigen Test) because, while all Toronto students had been given RATs and instructed to test for COVID-19 positivity every 3-4 days over the 2021-22 winter break, there was no mechanism for reporting this data and making it available at the level of individual schools. The RAT tracker, however, also illustrated the limits of such work: The Local shut it down within two weeks because while the data was consistent with overall COVID-19 rates, the lower participation rates from a voluntary reporting mechanism meant that the picture at the individual school level was not granular/accurate enough to be a robust tool for parental decision making (Huynh & Hune-Brown, 2022).

Much of The Local’s investigative reporting and many of its in-depth features flowed from its data work. As journalist Fatima Syed described it, the approach was “people and data,” that

The Local was seeing it and collecting it at such a granular level that it was undeniable, that Jane and Finch was going to be hurting the most right now. And if that’s what was happening, instead of just writing that Jane and Finch is hurting, let’s go to Jane and Finch and understand why is it hurting? What do they need? Who are the people who are hurting? And let’s tell that story right. (personal communication, May 17, 2023)

This approach led to stories like “The 35 Jane,” which follows essential workers and other commuters on a crowded bus line during the height of the pandemic, and to Syed’s award-winning feature “You Can’t Stop the Spread of the Virus if You Don’t Stop it in Peel.”

Community connection

Across multiple registers, The Local did an excellent job of building trusting, long-term relationships with different communities. These relationships arose from the unique structure, policies, and history of The Local.

Incubation at OpenLab

The Local began as a hyperlocal storytelling project of OpenLab, an incubator within the University Health Network, a multi-site, state- of-the-art research hospital affiliated with the University of Toronto. Its first employees were not originally journalists, but scientifically trained people involved in health research and policy, who were part of the public health community and had relatively good access to health statistics and data. One of the anonymous health sector interviewees described how he considered Tai Huynh a colleague whom he texted and called, rather than a journalist. Particularly considering the earlier-described ‘chill’ that many public health workers felt around their ability to speak publicly about their concerns, having Local staff who were ‘insiders’ who also worked within the public health system, made a considerable difference.12Tai Huynh and The Local’s Manager of Operations Craig Madho were both affiliated with the OpenLab prior to working at The Local, and continued to be so after The Local became independent in 2019. City Councillor Joe Cressy, Chair of the Toronto Board of Health, and member of the City of Toronto’s COVID-19 Strategic Command team and Immunization Task Force, described The Local as having “strong ties” within the public health community. Through his work with OpenLab, Huynh was involved in the behind-the-scenes of organizing community and mass vaccination clinics, which were extensive logistical endeavors. This connection gave The Local both more access to, and a deeper understanding of, how these clinics ran. It was therefore able to feature in-depth, timely, on the ground coverage of community vaccination clinics.

Solutions journalism

In turn, The Local’s presence at these clinics built trust with local communities. Tai Huynh ‘live-tweeted’ from community mass vaccination clinics, showing volunteers and staff at work, and highlighting the number of people vaccinated on a given day. Photo essays like “Bringing the Vaccine to Where it’s Needed,” which featured the voices of residents getting vaccinated at a pop-up clinic in the forward sortation area/postal codes with the lowest vaccination rate in the city, a Toronto neighbourhood known as Jane and Finch, pushed back on the narrative that the community was vaccine hesitant. Rather, throngs of people were relieved and happy to be vaccinated, once structural barriers (such as not having a health card) were removed. Multiple interviewees in the public health field, some themselves members of racialized communities, mentioned how the portrayal of public health successes in ‘hot spot’ neighbourhoods, such as the feature “Getting Vaccinated in the Holy Month,” was a breath of fresh air for communities that were often portrayed negatively. As part of The Local’s practice, article subjects were always sent a final copy upon publication, to read and share as they found appropriate. This type of solutions journalism was not only helpful for professionals advocating within public health structures for vaccination equity: consistently showing the achievements of community leaders and community volunteers in hard-hit neighbourhoods built trust with racialized communities and grew The Local’s audience. Figure 3, a tweet from Sophie Ikura, founder and Executive Director of Health Commons Solutions Lab, offers an example of The Local’s work reaching, and influencing, people in a hard-hit north Toronto neighbourhood.

Figure 3. Sophia Ikura tweet

Figure 4, a retweet from Tai Huynh of a tweet from the nightly Punjabi language TV broadcast of OMNI, a multilingual television station, is another. The featured doctor, who is speaking about racism within the health care system, is wearing a “Here for M1B” t-shirt: The Local had reported from the first pop-up clinic in M1B, or the Malvern neighbourhood, a COVID-19 hot spot. Tai Huynh had printed up and given out these shirts to staff and volunteers working at Malvern vaccination pop-ups.13The Local gives donors a similarly designed t-shirt, displaying “Here for YYZ,” the code for Toronto’s Pearson International Airport.

Figure 4. Tai Huynh tweet

Structural commitments to racial equity

Nicolas Hune-Brown described that

73 percent of The Local’s contributors self-identify as being racialized, which is unheard of in Canadian media, especially in Canadian media that isn’t the ethnic press. . . . We make a commitment each year to support young journalists, emerging journalists, BIPOC, to really establish a strong footing in industry. (personal communication, August 25, 2022)

The Local has a Race, Representation and Equity Commitment, and regularly reports how it is implementing the policy and hitting its targets. The Local assigns stories and builds its roster of journalists based on a belief that reporters who have the tightest connection to a community can report on it best. During the pandemic, The Local launched a fellowship program that Executive Editor Nicolas Hune-Brown described as having interrelated goals for its first cohort: to foreground the experiences of hard-hit and little featured Toronto neighbourhoods by mentoring and training aspiring journalists who were from and therefore understood these communities. The issue prior to the Vaccinating Toronto issue, the Winter 2021 issue Pandemic Faultlines, was a culminating project for the fellowship journalists. Through the fellowship program, which has continued in subsequent years, The Local aims not only to develop a sizeable pool of racialized journalists with close connections to underserved communities in the GTA, but also to support a ‘pipeline’ for BIPOC journalists to build their skills and take up more prominent positions throughout Canadian media.

A commitment to following community issues long term

The Local’s pandemic coverage is one example of the magazine following subject matter long term: six issues of The Local, over the course of two years, addressed how the pandemic impacted GTA communities. This coverage sustained multiple long term narrative arcs, such as looking at disparities in COVID-19 rates and vaccination in schools; following the progress of mass vaccination campaigns in hot spot neighbourhoods; and examining ongoing risks in congregate settings such as public transit.

The Local’s mandate, to cover social determinants of health, means that it comes back again and again to key issues, such as homelessness or structural barriers Black Torontonians experience in accessing public services. This is reflected in the thematic structure of issues—for example, ‘day in the life’ issues, that take the pulse of the city at a particular time, whether in pandemic circumstance or looking at shift workers and others awake at 3 a.m. The Local builds community relationships over time through this enduring presence.

Stable yet flexible funding

OpenLab, where The Local was incubated from 2017 to 2019, is an innovation hub funded by the University Health Network. Because The Local didn’t need to be immediately self-supporting, it was able to experiment with formats and approaches, focusing on quality journalism and on building the organization and its relationships. In September of 2018, The Local met with several important Toronto area foundation funders, with a series of Local stories from various Toronto neighbourhoods as proof of concept. Multiple foundations agreed to pool their resources and provide The Local with three years of start-up funding as “trust-based philanthropy” (Huynh, 2024). This allowed The Local to be nimble in the unprecedented pandemic situation, pivoting from quarterly publication to a more responsive model, with articles appearing on a rolling basis, even as groups of articles would form one ‘Issue.’ Being able to focus on producing the most appropriate journalism in turn helped The Local build a greater supporter base. Since gaining charitable tax status in 2022 as a Registered Journalism Organization, The Local has aimed to diversify its funding base to include more small individual donor supporters.

Multiplier effects

The Local offered quality information not accessible elsewhere, and built strong relationships of trust within key communities. However, for The Local to extend its reach and influence, several contextual factors were at play, as described below.

Amplification through social media and through other journalism outlets

As per Chen and Roburn (2025), The Local substantively grew its following through Twitter, as posts by The Local and its journalists were repeatedly shared, bringing The Local’s journalism to the attention of new audiences. Facebook helped in connecting with parents who were a key audience for the School Tracker.

Racialized journalists, including Syed, emphasized that for racialized journalists who faced structural barriers to participation in mainstream media, Twitter and other social media were important channels for accessing audiences and building their profiles, and for marginalized people to tell their stories and shape broader narratives. Local freelancer Syed’s personal following over Twitter was another route for Local features to reach new audiences. More generally, journalists and journalism outlets played a significant role in The Local’s Peel coverage gaining wide traction. They both shared Local stories over social media, and had Local reporters as interviewees in their TV and radio stories, reaching mainstream audiences. For example, Syed spoke multiple times on the CBC, Canada’s public broadcaster, about the crisis in Peel, including as a featured guest on the daily early morning CBC radio national affairs talk show, The Current.

As the pandemic wore on, and some doctors built a social media following as “self-styled experts” who were perceived to have their own agendas, trust declined in ‘pandemic Twitter.’14This was discussed at length by a health reporter who wished to remain anonymous, in relation to the challenges of finding medical professionals who were accessible and willing to speak on the record, without returning to the same voices all the time. Fitzpatrick et al. (2022) also describe the phenomenon of certain medical professionals becoming household names in Ontario due to their establishing themselves as COVID-19 ‘experts’ through media and social media Yet The Local kept its influence. The tweets of Editor-in-Chief Tai Huynh, in particular, were generally perceived to be fact-based and credible, rather than agenda or personality driven.

Collaboration with The Toronto Star

The excellence of The Local’s data journalism led to collaborative reporting published in The Toronto Star, the main Toronto-based newspaper. The first of two major data-based collaborations appeared in early June 2021, a few days after the six-month period that was the focus of the social media component of this study. However, multiple interviewees mentioned the collaboration15Kenyon Wallace highlighted two major collaborations: the Hot Spot collaboration described in the quote and a separate collaboration that assigned COVID-19 risk scores at the individual school level for every city elementary and middle school. as widening the reach of The Local’s journalism. In the words of The Star’s Kenyon Wallace:

we had seen Tai do a really cool graphic looking at vaccination in hot spots versus non-hot spots over time, it was like a moving graphic, it’s actually a flourish chart. And we had not done such a thing. We knew him well enough to approach him to ask if he would be willing to team up with us to share that with us, partly because it’s a very, very useful, interesting way to show the data. And we felt that it was important that as many readers as possible get to see that. . . . [It] would be beneficial to the public. . . . So we did this big feature on looking at vaccination rates in the areas that were deemed hot spots by the province in terms of those priority neighborhoods that were targeted for vaccination, and also areas that had had disproportionate rates of infection. And so luckily, for us, he agreed, and we were able to publish that piece, which I think worked out really well. (personal communication, August 25, 2022)

This passage shows clearly that The Local was seen as a data journalism innovator. It also highlights a more collaborative rather than competitive approach to news gathering, and underlines a service journalism orientation that emerged in much pandemic reporting.

No paywall

The Local’s site is free and accessible to anyone with an internet connection. This made its journalism more accessible for the marginalized communities featured in its journalism.

Quantitative analysis

Journalists interviewed, both from The Local and elsewhere, made multiple statements that The Local influenced the coverage of the roll- out of vaccinations in the GTA towards a greater focus on vaccination equity and on Peel and other underserved regions. Social media analysis, as per the first phase of this study (Chen & Roburn, 2025), has evolved methods for quantitative analysis of certain types of influence, for example by looking at number of times a message is shared and analyzing the links/networks by which information circulates. However there is not the same kind of developed analytical method for empirically establishing how one news publication’s coverage might influence another’s. Without the more direct demonstration of information ‘flows’ available with social media analytics, one cannot have certainty, even if there is correlation between two publications, that one ‘caused’ influence on the other. However, arising from the interview findings was a clear inflection point for the interviewees claims of a change in coverage: the publication of “You Can’t Stop the Spread of the Virus if You Don’t Stop it in Peel” on April 22, 2021, one of three Peel-based investigative stories for The Local for which Fatima Syed won the 2022 Press Freedom Award from World Press Freedom Canada (WPFC). It is possible to investigate if Peel region received more coverage after the publication of the article, and if the coverage shifted towards more of a health justice frame.

To investigate this claim empirically, all articles mentioning COVID-19 and Peel and/or Brampton and/or L6P (the forward sortation area for Brampton in Peel region) published in two major papers, The Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail, were compared for two time periods: six weeks before Syed’s article was published and six weeks after. Articles where the pandemic was mentioned incidentally were discarded. The relevant articles were analyzed in two ways.

Firstly, articles were categorized by overall number and length, to see if the amount of coverage increased. As COVID-19 mentions declined in both papers in the second time period compared to the first, for the purpose of this analysis, the two periods were compared in terms of the relative frequency of discussion of the Peel region and of specific frames such as health justice within overall pandemic reporting.

As seen in Table 3, The Star increased its relative coverage of the pandemic in Peel after April 22.16One Star journalist was careful to note that the paper, independent of The Local’s interventions, had a long-standing commitment to health reporting and to adopting an equity perspective. As an example, on April 22, the day Syed’s article ran, an article in The Star celebrated reporter Sara Mojtehedzadeh’s win of an Amnesty International Media Award for her work on rights and working conditions in Amazon warehouses in Canada. Before April 22, The Star did significant work reporting on a COVID-19 outbreak at an Amazon warehouse in Peel, where over 600 workers fell ill In the six weeks after Syed’s article, the number of articles with relevant mentions of the Peel region’s pandemic experience stayed relatively the same (28 articles before, 30 after), despite a decline in overall pandemic coverage. More dramatically, articles with a clear focus on the Peel region jumped from 16 to 25. Overall, articles discussing the Peel region increased in the second period, from 1.2 % of articles mentioning COVID-19 to 2% of the total. When length of articles, used as a proxy for depth of coverage, is taken into account, the increase between time periods is less pronounced. While articles with significant mentions of Peel increased in overall length, the increase in focused articles on Peel skewed towards shorter articles; numbers of medium and longer articles stayed largely the same, but there was a significant increase in short articles.

Table 3. Coverage of Peel/Brampton/LP6

| Article source and category | Length of articles | Six weeks prior to April 22 | Following six weeks |

| Globe and Mail | |||

| Mentions | |||

| short | 5 | ||

| medium | 11 | 7 | |

| long | 2 | 2 | |

| Clear focus | |||

| short | 3 | ||

| medium | 4 | 7 | |

| long | 2 | 3 | |

| Toronto Star | |||

| Mentions | |||

| short | 12 | 9 | |

| medium | 15 | 14 | |

| long | 1 | 7 | |

| Clear focus | |||

| short | 3 | 11 | |

| medium | 8 | 10 | |

| long | 6 | 5 |

Shifts towards greater coverage of Peel region in The Globe and Mail were more equivocal, which is to be expected as The Globe is a national paper rather than one focused on the GTA. In the post- April 22 period, the number of articles with a clear focus on Peel region rose very slightly in The Globe and Mail (from nine to 10), despite a roughly 14% overall decline in pandemic coverage. However overall, Peel coverage declined from 2.6% of overall coverage mentioning COVID-19 to 2%, with the number of articles with relevant mentions (at least two to four sentences analyzing specific issues in the Peel region) halved. While there were fewer articles discussing Peel region in the second period, they skewed overall longer. No articles in the second period were classified as short (either mentions or focused category) increasing the overall average length of articles as long articles were the same in the two periods.

The second part of the quantitative analysis sought to discover if after April 22 more articles followed The Local’s lead in telling first-person stories—for example, of a thirteen year old child of an essential worker who passed away from COVID-19 in Brampton—and in taking up a health justice frame. Articles were classified as taking up a health justice frame if they echoed perspectives taken in various Local articles about pandemic issues such as an emphasis on high rates of COVID-19 among essential workers who lacked sick pay, or concerns about equity in access to vaccinations. Overall, after April 22, both papers increasingly used health equity frames and told the stories of individuals living in the Peel region as part of their reporting. The Globe and Mail shift is slight: the main difference between the two periods is that The Globe began to use the frame of ‘hot spots,’ meaning structurally disadvantaged areas/neighbourhoods where the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic were more severe. The Toronto Star had a more significant 57% increase in articles that used a health equity frame. The Star also had a 50% increase in reporting that drew on personal narratives of ordinary people living in Peel region, with two-thirds of these articles having a health equity framing. Given the relatively small number of articles in the sample, it is difficult to be definitive about these effects. However, overall, the results are consistent with and support the multiple testimonies given by journalists and health advocates in this study that Syed’s article helped catalyze more in-depth coverage of the pandemic in Peel region from mainstream media locally, and a shift towards health justice and personal storytelling frames within the reporting.

DISCUSSION

Although it is a relatively small digital news startup of modest resources, the results of this study suggest that The Local had a significant impact on COVID-19 vaccination and health policy in the GTA in the January to June 2021 period. This directly impacted the lives of tens of thousands of people in underserved GTA communities, who were able to access vaccinations and reduce their exposure to serious illness.

In this instance, The Local was successful in carrying out its mandate of covering urban health and social issues by filling “a role that traditional media neglects—turning complex policy issues into compelling narratives, and addressing problems that are systemic and ongoing, even if they don’t have a news hook” (The Local, 2025).

The “method” by which The Local achieved these results is complex. Many findings–such as a focus on collaborative and solutions-based journalism– resonate with other research into digital journalism start-ups. At the same time, it can be argued that The Local has evolved a unique approach. Reporting has a clear perspective (or agenda) of a health justice lens, but at the same time is data-driven. Data itself, presented succinctly and clearly, starkly surfaces unequal health outcomes, prompting important policy questions regarding how such unequal outcomes could occur. The Local then provides context for the issue (in this case, pandemic health outcomes) through deep feature reporting by and with communities. Such reporting showcases community-based solutions where possible, and often brings in experts to provide background and explain policy options.

This approach upends assumptions of traditional models of journalistic objectivity, which equate taking a perspective with bias and with distorting, rather than serving, accuracy and truth. The Local is by no means unique in this. Such changes to journalistic ethics and approaches are seen in many new journalism start-ups (Callison & Young, 2020), and in forms of reporting that have evolved to address climate change (Dunwoody, 2015). In the case of The Local, truthful, contextually appropriate and fact-based reporting arises through an ethics of accountability, transparency and representation. These ethics are not just in the reporting, but built into The Local’s structure and practices. Along with the previously discussed Race, Representation and Equity Commitment, The Local has a Code of Ethics, publicly available on The Local’s website, that makes specific commitments to accuracy, editorial independence, and transparency—for example, The Local publishes a list on its website of the sources of all donations over $5,000.

More research is needed to see if this “method” applies to how The Local reports on other ‘systemic and ongoing’ population health emergencies, and if it is effective. Unlike a pandemic, which evolves relatively rapidly and has impacts that cut across society, concerns such as the opioid crisis and urban heat/climate change impacts are examples of ‘slow violence’ (Nixon, 2011), and are notoriously hard to draw attention to in a news milieu focused on the urgent and spectacular. There is anecdotal evidence that new types of journalism ventures are finding ways to successfully foreground such slow violence issues. For example, The Baltimore Banner, a digital community news start-up based in Baltimore, won a 2025 Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the fentanyl crisis. This journalism resembled The Local in that it had a collaborative element (with The New York Times fellowship program); involved data journalism that accessed and made legible and public a set of records that the government was reluctant to turn over; and focused on the health equity dimensions of the crisis, which disproportionately affected older Black men (Boteler, 2025). Crackdown, a podcast about the toxic drug crisis produced by and for drug users, offers another example. The podcast not only shot to the top of the Canadian iTunes podcast charts, but has won numerous awards, and been featured in mainstream media and even in The Columbia Journalism Review (Mullins, 2025).

To the degree that The Local is a successful example of a small journalism start-up growing in the gaps left by the dramatic decline of community journalism in Canada in recent years, one must ask if this success is replicable, if it is scalable, and what its limits are. Answers to some of these questions are as yet unclear, and depend on policy choices and journalistic innovation. For example, while only certain journalism start-ups are likely to be able to attract substantive ‘start-up’ funding as The Local did, changes to government funding models can help most journalism start-ups. In Canada, a coalition of such start-ups were a part of conversations with the federal government on eligibility for journalism support funds and tax credits. Registered Journalism Organization status, which first came into effect in 2020, allows a news organization to offer charitable tax receipts for donations it receives. The diversification of revenue sources for journalism start-ups is a larger discussion, but The Local’s staged approach—wherein it could focus on building its community relationships and its journalism, and seek to diversify to subscriptions and other revenue sources once more established17The Local has launched The Local StoryLab, a paid service whereby Local journalists produce stories for mission-driven organizations to host on their websites. The earnings go to supporting The Local.—is instructive.

This study underlines the increasing relevance of data journalism, even for small journalism start-ups. The loss of community journalism outlets contributes to local issues being under or unreported, and data can surface such issues – this ‘scales up’ beyond The Local’s experiences in Toronto. Luckily journalism education is shifting accordingly, and innovative partnerships such as the Local News Data Hub—wherein journalism students identify and process newsworthy data sets, and use a semi-automated process to create stories populated with data targeted to specific communities, available through a wire service—are lowering the costs and structural barriers to accessing data journalism. However, this type of hyperlocal data journalism depends on relevant data being publicly available. This can be a significant constraint, especially where governments do not wish to disclose information. Although this study suggests that social media can play an important role in disseminating and popularizing stories from community journalism start-ups, it is difficult to apply this finding when the Canadian social media landscape has changed since the study period; Meta (and thus Facebook, Instagram, and Threads) no longer allows links to Canadian news stories, and the parameters and audience of Twitter, now rebranded as “X,” has altered substantively.18As an example of the impact of these changes, in 2019 40% of The Local’s traffic came through Facebook links. By the end of 2023, that percentage was zero. See https://thelocal.to/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/The-Local_Impact-Report-2023-1.pdf However, the results do point to the importance of further research and policy innovations with regards to one paradox of social media: the dilemmas posed to racialized and female-identified journalists. Racialized and women journalists in this study stressed that social media was an important pathway to accessing audiences; at the same time, such journalists experienced significant levels of harassment, disproportionately to white and male peers. Online harassment is not only a stressor that requires emotional labour, but produces a significant time penalty for journalists who must report threats to police and engage in other procedures such as responding to inappropriate complaints.

Larger media organizations may have an ombudsperson to deal with complaints from the public, so journalists have limited interface with an irate audience. They may also have more resources to devote to information technology supports which can also minimize journalist exposure to harassment. While small start-ups can support some individual-focused measures to counter harassment, such as better training for freelancers in securing one’s online profiles and managing social media accounts to minimize exposure, they are less able to insulate racialized and women identified journalists from hate. A more global solution for such online hate and harassment is effective platform regulation. This is a broader social issue, but it should be noted that better platform regulation is actually crucial to the flourishing of a more equitable news ecosystem.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study resonate with much current research characterizing how not-for-profit digital news startups are evolving within the broader journalism landscape. In focusing on The Local, an online magazine which explicitly takes an intersectional focus not only in its content but in its own workings, the research furthers understandings of how intersectional approaches can play out in digital news start-ups. It contributes to several ongoing research conversations about journalism startups. These include discussions of the ways hyperlocal digital journalism disrupts the geographies of power that play out in traditional news media (Downman & Murray, 2018); explorations of the “service journalism” turn of startups (Appelgren & Linden, 2020) and digital/data journalism (Widholm & Appelgren, 2020), which is especially germane in the context of underserved communities where relevant civic information is the least available; and observations of how dynamics of gender, colonialism and technology intersect in how a social purpose digital news startup pursues journalistic innovations to meet the needs of traditionally neglected audiences (Young & Callison 2017).

Further, this case study concretizes the real- world impact of a particular digital journalism start-up’s news coverage in one ‘hyperlocal’ area. While marginalized communities frequently object to mainstream media coverage that stereotypes and stigmatizes, blaming communities for social problems while obscuring the relations of power that create structural disadvantage (Zappia & Cheshire 2014), little research specifically demonstrates that more apposite journalism has made a material difference in social policy and in the day-to-day lives of community members. This case study, in providing tangible evidence of significant positive impacts, in this instance on health policy and health equity metrics, supplements the largely anecdotal illustrations of impact that not-for-profit journalism start-ups furnish to insist upon their worth to funders.

As traditional infrastructures of community news sharing continue to decline, this research offers a kernel of hope that hyperlocal digital community journalism can not only help alleviate ‘news deserts,’ but can offer a type of journalism that is more relevant and more equitable.

ENDNOTES

1. The Local News Research Project website (https://localnewsresearchproject.ca/) documents the state of local news in Canada through multiple means, including a variety of “news maps,” various written publications and newspaper articles, and downloadable data.

2. In Canada, anti-vaccination discourse became an important talking point for the far right, leading to convoys of truckers blocking a border crossing and taking over the streets of Ottawa for several weeks. See https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/key-events-canadas-trucker-protests-against-covid-curbs-2022-02-19/ and https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/how-american-right-wing-funding-for-canadian-trucker-protests-could-sway-u-s-politics. For the role of Russia in stoking these protests over social media, see https://doi.org/10.21810/jicw.v5i3.5101

3. The Strategic Command Team was tasked with coordinating the city-wide response to the pandemic.

4. The Local shared that the total viewership over the Tracker’s active lifetime was equivalent to the viewership for an entire multi-story regular edition of The Local. The Tracker also circulated widely through being heavily featured in Tai Huynh’s personal Twitter feed—raw data from the earlier social media analysis phase of this project showed 13 of his 100 most like Tweets discussed hot spots, with several linking directly to the Tracker.

5. This was the colloquial name used by interviewees for the data visualization. The visualization mapped densities of COVID-19 infections per forward sortation area, while toggling between displaying all pharmacies in the city and showing only pharmacies which were giving COVID-19 vaccinations. Disadvantaged areas with high covid rates did not lack for pharmacies, but a strikingly low percent offered covid vaccinations compared to pharmacies in wealthier neighbourhoods.

6. During the pandemic, one of the pivots The Local made to be more responsive in the moment to changing pandemic conditions was to experiment with publishing an issue as a ‘series’ over a period of weeks as individual articles were completed.

7. The exact figures are proprietary, although the author has access to them.

8. In cases where reporters worked at outlets that could be seen as direct competitors, and they are essentially comparing their own employer’s work unfavourably to The Local’s, I have omitted identifying details.

9. This claim was made by both Nora Loreto and an anonymous health journalist interviewee, referencing specific examples such as concerns about reporting on COVID-19 cases in long-term care homes.

10. The interviewee began by saying a few outlets had done data in the pandemic exceptionally well, then they mentioned The Local by name.

11. Tai Huynh described the page views as in the 100,000 range, and since the thousands of data points were reported to The Local by parents themselves (how many COVID-19 positive tests there had been that week at individual GTA schools), it is likely that most viewers were parents.

12. Tai Huynh and The Local’s Manager of Operations Craig Madho were both affiliated with the OpenLab prior to working at The Local, and continued to be so after The Local became independent in 2019.

13. The Local gives donors a similarly designed t-shirt, displaying “Here for YYZ,” the code for Toronto’s Pearson International Airport.

14. This was discussed at length by a health reporter who wished to remain anonymous, in relation to the challenges of finding medical professionals who were accessible and willing to speak on the record, without returning to the same voices all the time. Fitzpatrick et al. (2022) also describe the phenomenon of certain medical professionals becoming household names in Ontario due to their establishing themselves as COVID-19 ‘experts’ through media and social media.

15. Kenyon Wallace highlighted two major collaborations: the Hot Spot collaboration described in the quote and a separate collaboration that assigned COVID-19 risk scores at the individual school level for every city elementary and middle school.

16. One Star journalist was careful to note that the paper, independent of The Local’s interventions, had a long-standing commitment to health reporting and to adopting an equity perspective. As an example, on April 22, the day Syed’s article ran, an article in The Star celebrated reporter Sara Mojtehedzadeh’s win of an Amnesty International Media Award for her work on rights and working conditions in Amazon warehouses in Canada. Before April 22, The Star did significant work reporting on a COVID-19 outbreak at an Amazon warehouse in Peel, where over 600 workers fell ill.

17. The Local has launched The Local StoryLab, a paid service whereby Local journalists produce stories for mission-driven organizations to host on their websites. The earnings go to supporting The Local.

18. As an example of the impact of these changes, in 2019 40% of The Local’s traffic came through Facebook links. By the end of 2023, that percentage was zero. See https://thelocal.to/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/The-Local_Impact-Report-2023-1.pdf